Published in Mediterranean Quarterly: Fall 1997 & The Guardian, 30 July 1999

The Role of the United States in the Krajina Issue

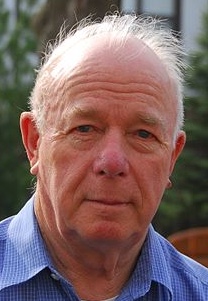

David Binder

(New York Times 1961 to 2004, Balkan Correspondent based in Belgrade 1963 to 1966 & 1990-92)

When Krajina fell in 1991 to Serbian forces—a combination of local militias and a strong Serb-led remnant of the Yugoslav Peoples Army—there was little outcry in the United States except, predictably, in the Croatian emigre community. One reason for the lack of concern was that attention was focused on far more dramatic confrontations in southern Dalmatia over Dubrovnik and in eastern Slavonia over Osijek and Vukovar, all of which evoked periodic ritual bleatings of dismay by administration spokesmen.

A second strong reason for the lack of U.S. solicitude for Krajina was that the Bush administration had, in effect, turned its back on the Yugoslav conflicts, beginning in the last week of June 1991. The policy of distance was adopted by Secretary of State James Baker in the aftermath of his disastrous meetings with all of the major Yugoslav leaders in Belgrade. He felt betrayed by the Croats and Slovenes, who announced their secessions from the Yugoslav federation a week after meeting with him.1

It should also be kept in mind that at the start of the fight for Krajina, the Yugoslav state still existed; Croatia’s declared independence had yet to be formally recognized by anyone, meaning that from the perspective of outsiders, the conflict was still being conducted in a Yugoslav context.

At Baker’s behest, the United States withdrew from the South Slav arena, leaving the next stages of combat to the luckless ministrations of the European Community. Not until the United Nations entered the scene in the person of Cyrus Vance as the personal envoy of Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali did an armistice between Serbs and Croats emerge, eventually to be maintained in the presence of UN peacekeeping forces.

(1. James A. Baker, The Politics of Diplomacy (New York: Putnam, 1995), 635-36.)

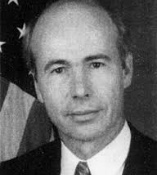

In 1992 and 1993, the Krajina issue became almost dormant as the international community concentrated on trying to deal with the violence that had erupted in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This state of affairs changed almost tragicomically when Peter Galbraith became the first U.S. ambassador to Croatia. Until his arrival in summer 1993, Croatia’s only powerful foreign advocate was Germany.

Known previously as a pro-Muslim activist on the staff of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Galbraith now turned his attentions to the Zagreb government and was soon lovingly portrayed in the Croatian press as he toured battlefields, even defying proprieties by showing up inside Herzegovina atop a Croatian tank. 2

He soon ingratiated himself with President Franjo Tudjman, with Tudjman’s son, Miroslav, who had become his father’s national security adviser, and with Defense Minister Gojko Susak. Purportedly, during his early meetings with Croatian officials he shared U.S. intelligence data. 3 In other circumstances, this might have prompted an uproar in Washington, but Galbraith had the advantage of going with a flow that included strong pro-Croatian sympathies in the Congress, particularly in the office of then Senate Minority Leader Robert Dole and in the National Security Council. In fact, the ambassador did become the subject of an investigation of intelligence leaks by the inspector general of the Department of State in autumn 1994, but the probe petered out, possibly because of discouragement by the executive branch. 4

Galbraith’s hand was greatly strengthened early in 1994 when the Clinton administration strong-armed President Tudjman and Bosnia’s Alija Izetbegovic to end the violent clashes between Muslim and Croatian forces in central Bosnia and Herzegovina and to support a Muslim-Croat “federation.” The aim was to create a bloc that at the very least would counterbalance the Bosnian Serbs, who controlled 70 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Tudjman acceded to what was for him an utterly distasteful federation with the grudging condition that the United States acknowledge Croatia’s right to “recover” its territories from the Serbs.

(2. Globus, 20 June 1993.

3. Two Clinton administration officials, confidential interviews with the author, Washington, D.C., 11 June 1996 and 18 November 1996.

4. Member of the Office of the Inspector General, confidential interview with the author, Washington, D.C., 10 October 1996.)

At this point, according to Bogdan Denitch, professor of sociology at the City University of New York, “the United States replaced Gemmany and the European Community as the major ally of the Croats.” 5

With demonic energy, Ambassador Galbraith set about the twin tasks of cementing the new Zagreb-Washington connection and simultaneously acting as a broker for the “federation” between Zagreb and the Muslim leadership in Sarajevo—a federation largely created by Galbraith’s senior colleague Charles Redman, the Clinton administration’s special envoy for Bosnia. By April 1994, only a month after the so-called Washington agreement on the Bosnian federation, Galbraith played the key role in arranging the secret air transfer of arms from Iran to the Bosnians by way of Zagreb, with the personal blessing of President Clinton.

Among some officials at the Central Intelligence Agency, there remains a strong belief that Galbraith personally solicited funds from several Persian Gulf governments to fund the Iranian shipments, although he has denied this and almost all other allegations concerning this still murky affair. 6 By agreement, accepted by Galbraith, the Croats exacted a toll of at least 30 percent on these Iranian weapons before they were transshipped across Croatian-held territory to the Muslims, in a way similar to previous import arrangements.

Galbraith also was involved, although as a nay sayer, in the September 1994 conclusion to what has been described as a 325 million contract between the Tudjman govemment and Military Professional Resources, Inc., (MPRI) of Alexandria, Virginia, founded in 1987 by seven retired U.S. generals. This organization was to train the Croatian Army. 7 At the time, however, Galbraith objected to the deal, saying to colleagues that he did not approve of the idea of U.S. “mercenaries” becoming involved in the Balkan conflicts.

(5. Globus, 30 October 1995.

6. In summer and autumn 1996, committees in both the House and the Senate investigating Ambassador Galbraith’s activities conducted extensive interviews with Central Intelligence Agency officials. Their testimony remains classified. I was briefed by committee staff members as well as by intelligence officials. See House Committee on International Relations, Final Report of Select Committee to Investigate the US. Role in Iranian Arms Transfers to Croatia and Bosnia, 104th Cong., 2d sess., 1996; and Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, U.S. Actions Regarding Iranian Shipments into Bosnia, 104th Cong.. 2d sess.. 1996.erals. This organization was to train the Croatian Army.

7. At the time, however, Galbraith objected to the deal, saying to colleagues that he did not approve of the idea of U.S. “mercenaries” becoming involved in the Balkan conflicts.)

The deal with the Tudjman government was broached by the Croatian Embassy in Washington after Defense Minister Susak received a delegation of U.S. officers, including retired general E. G. Saint, who had handed Susak his MPRI visiting card in summer 1994 in Zagreb, according to a participant. The first twelve MPRI officers arrived in the Croatian capital in December 1994, and a subsequent contract was approved by the State Department. In the past, these officers would have been widely branded mercenaries, to employ Galbraith’s terrn. Apparently the only public application of that epithet was in the Washington Times.8

(8.Washington Times, 15 December 1996.)

The arrangement was underpinned by the conclusion of a military agreement signed in November 1994 in Washington by Defense Secretary William Perry and Defense Minister Susak, the former Ottawa pizza merchant from Siroki Brijeg (a stronghold of the fascist Ustashe in World War II). In a toast with several reporters attending, Perry praised Susak as one of the greatest men he ever met and treated him cozily thereafter.

By early spring 1995 it became clear that the Clinton administration had begun to view Croatia’s greatly strengthened armed forces as the key factor in changing the insoluble Bosnian equation—indeed of bringing that conflict to an acceptable conclusion. The fruits of ensuing intense cooperation between the Pentagon and the Croatian military, bolstered by the MPRI mercenaries, became evident in Operations Flash, launched 1 May, and Storm, launched 4 August 1995, in the central and western Krajina enclaves.

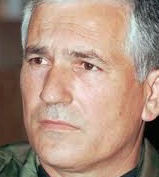

In fairness I should say that a U.S. officer familiar with the events contested to me the central role later attributed to the MPRI officers. Incontestably, the strategy and tactics of the Croats derived straight from the U.S. fighting design developed in the Cold War and known as Airland Battle— envisaging fragmentation of enemy formations into smaller units, disabling their communications, and then mopping them up. The U.S. officer who played down the role of MPRI asserted that the Croatian defense leaders had developed their own command-control capability under officers with NATO experience; General Ante Gotovino, who previously had served twenty years in the French Foreign Legion, serves as an example.

Contesting this thesis, however, a Croatian officer said of the MPRI after the second Krajina victory, “They lecture us on tactics and big war operations on the level of brigades, which is why we needed them for Operation Storm when we took the Krajina.” 9

(9 Observer (London), 5 November 1995.)

Then the morning operation—Storm—began, four U.S. Navy warplanes bombed two Krajina Serbian surface-to-air missile sites “near the towns of Knin and Udboma,” as Navy Times reported. 10 That eliminated danger to Croatian attack planes and helicopters. In addition, sophisticated communications technology was deployed in the offensive, some of it, according to the U.S. officer, possibly seized in 1991 from a Yugoslav Peoples Army installation near Zagreb, and some of it American. This technology was used to jam communications among Serb commanders and even to broadcast alarmist messages on Serbian civilian frequencies. 11 Finally, up-to-date U.S. intelligence from overhead reconnaissance and radio intercepts was made available to the Croatian leadership, according to the CIA, by none other than Ambassador Galbraith himself.

(10. Navy Times, 21 August 1995.)

That was not all. On a more visible level, Galbraith was in the port city of Split thirteen days before Operation Storm had even started, attending the signing of the military cooperation agreement between the Bosnian Muslim army and Croatia, which enabled Croatian forces to mount their assault on Knin from Livno.

(11. Slobodan Jarcevic, interviewed in Oslobodjenje (Serbian) 23 August 199S. Jarcevic is a cabinet adviser to Milan Martic, president of the Republic of Serbian Krajina.)

Then, on 2 August, in his role as the U.S. member of the so-called Zagreb 4, supposedly negotiating a deal between Knin and Zagreb, he met Milan Babic and extracted large concessions from him on Krajina’s future in Croatia. But this was a theatrical gesture aimed at preserving at least a shred of the Zagreb 4 option, of which he was a principal

To be sure, the Serb hold on Krajina was doubtless untenable due to paucity of manpower and resupply capacities and above all to the crippling policies of Slobodan Milosevic, the original godfather of Serbian Krajina, who had just replaced the Krajina commander with his own man, General Mile Mrksic. The marching orders given to Mrksic in Belgrade were apparently to give up rather than to defend the four-hundred-mile front.

Yet I believe it can be said that without the U.S. involvement, technical and professional, the fight for Krajina would have lasted a lot longer than the thirty-six hours it took the Croats to conquer Knin and the rest. Nor would the mass flight of Krajina Serbs amid shelling, torching of homes, looting, and killing of civilians (more than fifteen in Operation Flash alone, according to Serbian sources) have transpired in the fashion it did.

Did the United States give a blessing to the offensive? The administration sidestepped the question when asked publicly, although one official confided to me that Clinton had signaled with “an amber light turned green.”

But neither President Clinton nor Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke disguised his pleasure and relief over its success, the latter saying in following days that it “opened a window” for a solution to the Bosnian conflict.12 Croats were less cautious. On 8 August 1995, Stripe Mesic, a former president of Yugoslavia and later leader of the Croatian Independent Democrats, said that President Tudjman “received the go-ahead from the United States.”13 Two days later, Mate Mestrovic, a member of the Zagreb parliament, said, “The United States gave us a green light to do whatever had to be done.” l4 Again, Ambassador Galbraith was on the scene, driving alongside the desperately fleeing refugees, even climbing atop a Serbian tractor. (President Tudjman scorned this act then and later as “tractor diplomacy.”)

“It is not ethnic cleansing,” Galbraith told BBC Radio on 8 August, adding by way of gratuitous explanation that this term applied only to the actions of Serbs “sponsored by the leadership in Belgrade, carried out bythe Bosnian Serbs and also by the Croatian Serbs.”

(12. New York Times, 6 and 12 August 1995.

13. Panorama (Milan), 8 August 1995.

14.Le Nouvel Observateur, 10 August 1995.)

Later that day, David Johnson, the State Department spokesman, amplified this line by saying, “What’s gone on in the Krajina area looks to be departure of refugees.” Again, it was not ethnic cleansing, according to the Clinton administration line, because “I think there is some distinction between that and refugees leaving because they believe there might be a lack of safety there as distinct from being driven from their homes as a government policy.”

(15 David Johnson, State Department briefing, Washington D.C., 9 August 1995)

Later, after at least 170,000 Serbs had fled western Krajina, Ambassador Galbraith voiced polite concerns over Croatian atrocities in the Krajina campaign, saying he had been “appalled” by some of the reports, but nothing he or any other U.S. official said on the subject compared to their previous or subsequent expressions of outrage over Serb transgressions.

Nor was the United States in general or Ambassador Galbraith in particular rewarded by Croatia for all of the material and other assistance they provided. On the contrary, the Tudjman regime steadfastly rejected all U.S. pleas for lenience toward the Serbs of Croatia or anything resembling a turnabout of their campaign of ethnic cleansing in Krajina. Galbraith personally became public enemv number one to Franjo Tudjman. “He absolutely hates Galbraith,” another U.S. ambassador confided to me, “which is quite a reversal, since in the beginning, Galbraith was more Tudjman’s ambassador than he was ours.”

What struck me again and again as I examined the published material on this issue was the almost total lack of interest in the U.S. press and in the United States Congress about the size, quality, and cost of the U.S. involvement before, during, or after the Croatian conquest of Krajina. Nobody, it appears, wanted even a partial accounting, even on an off-the-record basis of the role of MPRI mercenaries, the actions of Ambassador Galbraith, or the participation of U.S. military and intelligence components.