INTRODUCTION

THE CASE AGAINST ATTACHMENT

There is a new school of war reporting taking over the media world, one which BBC correspondent-turned-MP Martin Bell has dubbed the Journalism of Attachment. It calls for war reporting which records human emotions and suffering as well as cold facts; journalism which, in Bell’s words, ‘cares as well as knows’.

The Journalism of Attachment says that reporters cannot remain detached or neutral in the face of modern evils like genocide in Bosnia or Rwanda, but must side with the victims and demand that something-must-be-done. The Journalism of Attachment might sound like a worthy appeal for concerned reporting. But it is a menace to good journalism – and to those whose lives it invades.

Rather than exposing the political and social roots of wars, the Journalism of Attachment depicts them as exclusively moral struggles in which Right Fights Wrong. It reduces complex conflicts to simple fairy tale confrontations between the innocent and the forces of darkness. To achieve that journalists have to appoint themselves as judges of who is Good or Evil in the world. And that means a journalist’s responsibility to report all of the facts can come a poor second to broadcasting what is considered the morally correct line.

The Journalism of Attachment is self-righteous. Worse, it is repressive. Those who fall the wrong side of the line the press corps draws between Good and Evil – the Iraqi Muslims, the Bosnian Serbs, the Rwandan Hutus – can expect to be on the receiving end of more than a bad press. The Journalism of Attachment demands that the wicked be punished, with UN sanctions, Nato bombs, International War Crimes Tribunals and SAS hit-squads. Nor do those whom the new school of war reporters claim to be defending – the Iraqi Kurds, the Bosnian Muslims, the Rwandan Tutsis – seem to have derived much benefit from the sponsorship of the world press.

But then, the Journalism of Attachment is not really for the benefit of anybody ‘over there’ in foreign war zones. Its primary function is to give a sense of purpose and self-importance to the reporters themselves, to help compensate for what feels like a moral vacuum over here in Western societies. At a time when many in Britain and America no longer seem sure about the meaning of right and wrong, foreign reporters are taking the easy option and trying to re-establish some moral certainties in relation to faraway places. In launching their mission to vanquish ‘evil’ in Eastern Europe or Africa, they are using other people’s life and death conflicts to work out their own existential angst, turning the world’s war zones into private battle- grounds where troubled journalists can fight for their own souls by playing the role of crusader.

For those who practise the ]ournalism of Attachment, reporting what is happening in the real world often seems to be of secondary importance to their spiritual quest. The central purpose of these Western reporters in slaying monsters in Bosnia or Rwanda, Chechnya or Wherever, is not so much to find out the truth as to find themselves, and so compensate for the apparent lack of worthwhile values in their own societies.

In the process, the war reporter emerges not as journalist but as combatant, not as news broadcaster but as the news itself, a singularly moral figure on a self-appointed mission to save the world. That might make some journalists feel better about themselves. But at what price for journalistic standards? Or for those unfortunate enough to be turned into cannon fodder for the media people’s personal crusades?

TAKING SIDES OR TAKING LIBERTIES?

There is nothing wrong with journalists taking sides on the issues and conflicts they cover. Having investigated and reported what is happening, they are as entitled as everybody else to let the world know what they think about it. What they are not entitled to do, however, is to get their evidence mixed up with their emotions, so that they risk seeing what they want to see rather than reporting all that is there.

There is a difference between taking sides and taking liberties with the facts in order to promote your favoured cause. There is a difference between expressing an opinion and presenting your personal passions and prejudices as objective reporting. And there is a difference between reporting from the midst of a conflict and writing as if you were the one at war, so that the journalists and their feelings become the news.

Those who pursue the Journalism of Attachment are in danger of committing all of these offences and more. Martyn Lewis of the BBC has been ridiculed by colleagues for his promotion of the concept of ‘happy news’. Yet many top foreign reporters are already effectively practising what Lewis preaches. They are headlining those stories which they believe present the ‘right’ moral message to the public, and downplaying those which give off the ‘wrong’ signals, regardless of which best meet the criteria of real newsworthiness. They are substituting sentimental human interest stories about their hand-picked victims for serious analysis of the wider causes of conflict.

The Journalism of Attachment is a kind of Happy World News Highlights for the chattering classes. Nik Gowing of BBG World Service Television has spoken of ‘a cancer now affecting journalism’, which he sees as the ‘unspoken issue of partiality and bias in foreign reporting’. Gowing notes that there is ‘something taboo, or even heretic, to talk about this in media circles, partly because to do so would undermine the perceived integrity and objectivity of correspondents who report from battlezones.’*

It is time that taboo was broken, and the unspoken issue of fashionable bias in war reporting was openly debated. Then it might be possible to set about cutting the cancer out.

WHO CARES, WINS

What is the Journalism of Attachment all about? Martin Bell defined the term in opposition to the tradition of war reporting in which he was trained, an approach he now calls ‘detached, uncommitted, neutral “bystander’s journalism”‘. Particularly since Bosnia, says Bell, war reporters are ‘no longer spectators, but participants’, with a responsibility to take sides with the victims, to defend good against evil, and to demand of governments and international agencies that ‘something-must-be-done’. He defines the Journalism of Attachment as ‘a journalism that cares as well as knows’, insisting that his profession is ‘a moral enterprise’ which ‘must be informed by an idea of right and wrong’ because the journalist is an actor with the ability to influence the outcome of the events he reports and ensure that ‘good prevails’.

Although few war reporters have publicly endorsed Bell’s explicit call for an attached journalism, many pursue a similar approach post-Bosnia. Top reporters like Roy Gutman of US Newsday, Christiane Amanpour of CNN and Ed Vulliamy of the Guardian, all of whom won major awards for their war stories from Bosnia, have argued that international journalists now have greater responsibilities than the mere reporting of facts, and that they have a duty to use their influence to combat modern evils like ethnic cleansing and genocide. Bell and Vulliamy became the first journalists to give evidence for the prosecution at the International War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague during the trial of the Bosnian Serb Dusko Tadic.

The new attitude demonstrated by some of the highest-flying foreign correspondents in the world signals a sea change in journalistic opinion. Of course, few war reporters have ever really been neutral. The British media, for example, has always been dominated by Empire Loyalists who looked at the world through red-white-and-blue coloured spectacles, ensuring that Britannia rules the air-waves and Johnny Foreigner feels the sharp end of the reporter’s pencil. In the past, however, major news organisations like Bell’s BBC felt obliged at least to pay lip service to the image of the reporter as detached observer during wars and other momentous events. What is now being said openly is that it is not only impossible for a journalist to be a dispassionate bystander, but that it is undesirable anyway. And what is more, it is being said by the kind of liberal-minded, ‘anti-establishment’ reporters who would be loud critics of old-fashioned patriotic bias in war reporting.

All of these reporters insist that the facts are still sacred and that, while they are not ‘neutral’, they do all they can to be ‘objective’. But then they would say that, wouldn’t they? After all they want recognition as serious journalists, not creative writers. Yet despite their denials, the evidence suggests that there is a clear contradiction between their formal commitment to the objective reporting of the facts and their moral attachment to what Roy Gutman calls the ‘higher requirements’ of getting the ‘right’ message across.

GOOD AND EVIL

For people who lay great store by the importance of being ‘down on the ground’ in a war zone, leading foreign reporters now seem to spend a great deal of their time trying to climb up onto the moral high ground. The stock-in-trade of today’s top war reporters is moralism: the attempt to depict Bosnia or Rwanda as morality plays in which Good battles Evil, an effect often achieved by describing these conflicts in apocalyptic terms as ‘Genocide’ or ‘another Holocaust’

These war reporters see fit to set themselves up as the Solomons of the cyberage, using their on-line laptops and satellite links to make instant yet final judgements as to who or what constitutes ‘the original sin and the unsullied virtue’ in the world. But in going down that road they are entering a journalistic minefield.

Good and evil are moral absolutes, and those who deal in that language can allow no room for the scepticism, nuance or critical questioning that are the working tools of good journalism. Instead of analysing all of the real forces and factors at play in any specific conflict, the moralisers have to impose a ready-made, one-size-fits-all-wars framework of Good and Evil. And having imposed their own rigid bIack-and-white framework on somebody else’s conflict, labelling one side as Right and the other as Wrong, there is an inevitable inclination to be more selective about reporting the story. Those facts which fit into their Good v Evil scenario might indeed be treated as sacred. The status of those facts that do not quite fit into the framework, however, can be much more negotiable.

Bosnia became the touchstone for the new school of war reporting, and the place where the dangers of the Journalism of Attachment were graphically revealed. From the first, the media moralised the civil war there in terms which one BBC journalist sums up as ‘the regular presentation of one side as bad (the Serbs) and one side as good (everyone else)’.

Nik Gowing, who was the diplomatic editor of Channel 4 News during the Bosnian conflict, has characterised the anti-Serb bias of the media as ‘a secret shame’ of the journalism community. The Bosnian Serbs were not just blamed for the war, they were demonised as barbarians, the new Nazis jackbooting through the Balkans, aliens from ‘the disturbed universe of evil’, running ‘satanic’ concentration camps.

Once that process of demonisation was underway, any notion of objective reporting of the conflict had to go out of the window. After all, who wants to hear the devil’s side of the story? And who cares much what happens to the devil’s disciples? Time and again, the international media suspended the normal standards of journalism in their fervour to present the Bosnian war as a straightforward battle between Good and Evil. Martin Bell himself concedes that the Sarajevo press corps exhibited a ‘generally crusading character’ against the Serbs, and that ‘most British soldiers, like most British journalists, never actually met a Serb from start to finish’, with inevitable results for the way in which the war was seen and reported.

Horror stories of Serb atrocities – death camps, rape camps, cannibalism, even Dr Mengele-type experiments on prisoners – were made into headline news, often on the basis of no more than uncorroborated and unchecked hearsay reports of the kind that always fly around war zones. Meanwhile top journalists and news organisations ignored or distorted any evidence which did not correspond with the battle cry of their moral crusade. Take just a few examples:

The Sarajevo market place massacre of February 1994, in which 68 civilians were killed by a single shell, is one of most infamous atrocities of the Bosnian war. It led to a hardening of attitudes in the West and the threat of the first Nato airstrikes against Bosnian Serbs. Yet a suppressed report by UN investigators implied that, in fact, Bosnian Muslim forces had fired the shell at their own people, in order to win international sympathy.

When Yasushi Akashi, former head of the UN mission in Bosnia, finally admitted the existence of this report in June 1996, he said that it was ‘no secret’ since ‘some journalists already had a copy’. Those intrepid reporters had kept the secret to themselves, ensuring that one of the biggest scandals in Bosnia remained effectively buried for more than two years.

Srebrenica became one of the world media’s favourite symbols of Serb aggression and Muslim suffering after the town was besieged by Bosnian Serbs in 1993. Since Srebrenica fell in 1995 horror stories of massacres and alleged mass graves have filled the news.

Yet who can recall seeing reports of the events which led up to the Serb assault on Srebrenica? Between April 1992, when the war in Bosnia began, and January 1993, Muslim forces drove almost every Serb out of Srebrenica town, while 50 nearby Serbian villages were burned down and many of their inhabitants killed. By March 1993, 1200 Serbs are estimated to have been killed, and about 3000 wounded, in this small corner of eastern Bosnia. Yet it was only when the ragtag local Serb army started to mobilise to push the Muslims back to Srebrenica and away from nearby Bratunac that the conflict hit the headlines. Suddenly journalists were flocking to get to the besieged Muslim enclave, having largely ignored the previous attacks on Serbs. The Muslims of Srebrenica and the Serbs of Bratunac both suffered. But while many in the West have heard of Srebrenica, who has heard of Bratunac?

Many media reports have claimed that 250 000 people were killed in Bosnia. Journalists have used these numbers to justify describing the civil war in hysterical terms as ‘genocide’ and even a ‘Holocaust’ against Bosnian Muslims. Yet the respected Stockholm International Peace Institute (hardly a pro-Serb organisation) puts the Bosnian death toll at a much lower 30 000-50 000 deaths on all sides combined.’ The inflated figure is simply Bosnian Muslim government PR, uncritically reproduced as hard copy by sympathetic journalists. Typically, Peter Maass of the Washington Post insists that 100 000 people were killed in Bosnia during his two years there, even though he admits that he only ever saw one corpse – an elderly lady who died of cold in a Sarajevo old people’s home.

One of the great war criminal stories of the Bosnian war was that of Borislav Herak, a Bosnian Serb who confessed to the mass murder and multiple rape of Bosnian Muslims and was convicted of genocide by a Sarajevo court in 1993.

Another Bosnian Serb, Sretko Damjanovic, was also convicted of genocide on Herak’s evidence.

John F Burns of the New York Times interviewed Herak in his cell before the trial (and won a Pulitzer Prize for his story), as did British Journalist of the Year Maggie O’Kane (and Bianca Jagger!). They reported his gruesome confessions around the world as hard fact.

Yet neither Burns nor O’Kane even bothered to mention that the clearly unstable Herak had also claimed that UN General Lewis Mackenzie was himself guilty of multiple rapes in Bosnia. Then, in June 1997, the credibility of Herak’s evidence was entirely destroyed, when two brothers whom he claimed Damjanovic had helped him to kill, turned up alive and well. The Sarajevo authorities, however, refused to reconsider Damjanovic’s conviction. The case also appears closed for Burns and O’Kane, since neither has yet written a globally-syndicated splash exposing the Herak scandal.

‘Witness L’ (real name Dragan Opacic) was the key prosecution witness who gave the International War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague details of the atrocities which his fellow Bosnian Serb Dusko Tadic was alleged to have committed at Trnopolje camp. But Opacic’s evidence (along with all the specific charges against Tadic relating to Trnopolje) had to be torn up when, having been confronted in court by the father he claimed was dead, he admitted that it was a pack of lies which he had been schooled to say in court while a prisoner of the Bosnian Muslim authorities in Sarajevo. Amid the countless thousands of words written and broadcast about Tadic’s trial and eventual conviction for war crimes, who noticed the name ‘Opacic’ get anything more than one quick mention on Channel 4 News?

None of the episodes which the world media failed to cover properly could have honestly been spiked on journalistic grounds. They included some potentially great news stories, genuine scandals, shocking revelations and moving human dramas. Their newsworthiness ought to have been beyond question. So why were they not covered in Britain and America, or relegated to the odd column inch or two on an inside page? The answer has to be, not because they failed to meet norma journalistic standards, but because they offended against the values of the Journalism of Attachment. The reporters and their editors imposed their own, external agenda in deciding which facts did and did not qualify as ‘news’.

The morally correct school of war reporting, pioneered in Bosnia, was quickly exported to conflicts elsewhere – most notably in Rwanda, when the civil war erupted into terrible bloodshed in 1994. Far away in Africa, Western journalists could give even freer rein to their prejudices and force the facts into their preconceived framework. The majority Hutus were branded as evil perpetrators of genocide, the Tutsis as innocent victims.

That uncompromisingly one-sided presentation of the local conflict was to have far-reaching consequences.

It meant that, once the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front came to power (thanks to US and British support) it was able to take bitter revenge against the Hutu population without fear of serious reproach from the press corps or the international community. Worse still, the media’s role in setting up many thousands of Hutu refugees in neighbouring Zaire as what one Guardian feature called ‘genocidaires’ left them open to being starved and then attacked with impunity by Zairean rebels backed by the Rwandan regime. The payoff of the Journalism of Attachment in Rwanda was not just lopsided reporting; it meant that the tragedy of those Hutu refugees was ignored or even justified until it was too late, at which point the press had the nerve to run a few breast-beating ‘Why-oh-why’ pieces.

SUFFERING FOR THEIR ART

Another claim made for the new approach to war reporting is that it is simply trying to adopt a tone that Martin Bell has called a ‘little bit more humanised and compassionate’, focusing less on the drawing-board strategies of armies and governments and more on human suffering among the victims of conflict on the ground. Elsewhere this has been described as a more ‘feminised’ school of foreign reporting, pioneered by a new generation of women reporters (but pursued by men and women alike).

‘I’m not interested in guns’, says Janine de Giovanni who reported from Bosnia for the Sunday Times, ‘I’m interested in people, how they manage to survive’.

Human suffering among victims is not hard to find in any war zone. It can make moving eye-witness news reports. The trouble is, however, that it cannot allow the journalist or her audience to make sense of what is happening, or why it is happening – especially when the suffering is only reported from one side of the conflict.

Maggie O’Kane of the Guardian was made Journalist of the Year on the strength of her highly-charged reports on the plight of victims in Bosnia. But why, she was asked in a television documentary, of the 50 or so articles she had written on the war in the former Yucoslavia from 1992-1993. had only one tried to explain the Serb point of view? “In retrospect”, she replied, ‘I could have seen more of the Serb side…But you gravitate to where the bigger story is. We were all in Sarajevo writing human interest stories’.

In an atmosphere where war reporting from somewhere like Bosnia means competing with other journalists to find the most dramatic human interest story on one side of the lines in one city, a clear view of the bigger political forces shaping events can easily become obscured by the emotional reaction. To understand why people are suffering, and see how it might be ended, you have to be able to put events in their wider context.

Some of the new war reporters are fond of making declarations like ‘I cannot be neutral between the artillery nest and the home it has just destroyed’. And of course, such moments of war horrify. But how are we to make sense of them? Instant reports from amid the rubble that focus only on tears will always tend to make warfare look like the apparently mindless act of evil men. To understand what that moment of violence was about, however, it has seen against the background of the months of political and military manoeuvring on all sides that finally brought those guns into play.

Martin Bell and others have often argued that the coverage of wars is now being ‘sanitised’ by the major news organisations, that shock-horror images of real atrocities are being suppressed on the grounds of ‘good taste’. No doubt they are right about that. But they are wrong to imply that demanding such images be shown is itself radical, challenging journalism, or that televising pictures of a mass grave at Vukovar can in itself expose the ‘brutish truth’ about the war in the former Yugoslavia.’ Pasted on the screen or the page as a snapshot, pictures of bodies piled up or burnt cannot inform, they can only touch the most hasic human emotions.

A challenging approach to exposing the truth would seek to investigate the whole story behind the pictures – not just who did it, but why – and put each act of violence in the political context which gave rise to it.

‘Political’ and ‘context’, however, seem to be dirty words among the journalists seeking human interest stories in Bosnia and elsewhere, many of whom are far more interested in emotions than analysis. ‘I am not a political reporter. I am not a diplomatic reporter’, says Christiane Amanpour of CNN: ‘I do wars; I do crises. I don’t do politics.’

Andrej Gustincic of Reuters goes further, describing how his concern to adopt what he saw as the victims’ point of view in Bosnia turned him from a political reporter into ‘what is called a colour writer…You don’t think about the political context, or your political views become really simple’. Simple, that is, as in black and white, Good and Evil.

And those facts which don’t fit into the media’s ‘really simple’ view of the conflict, which fail to press the right emotional buttons? They simply must be wrong. Misha Glenny, former radio journalist on the BBC World Service and author of The Fall of Yugoslavia, recalls how he sent the BBC the story of two massacres, one committed by Croats and one by Serbs. Guess which one the respected, impartial World Service reported, and which one it did not even mention?

Removed from the wider context of the war in this way, the only possible interpretation the audience could place upon events in Bosnia was that the Serbs really were evil. As Glenny puts it, in the absence of any serious explanation of why the Serbs acted as they did, ‘The general perception is because they are stark, raving, mad, vicious, mean bastards’.

By the last stage of the war in the former Yugoslavia the presumption that the Serbs were always the problem had reached the point where Martin Woollacott of the Guardian could say that the ruthless blitz by 100 000 Croatian troops on the Serb enclave of Krajina (which made 200 000 Serbs homeless, the biggest wave of refugees in the entire war), should be ‘welcomed as a hold on Serbian aggression’. The search for human interest stories removed from any wider context led the world’s press corps to treat one side in Bosnia as something altogether less than human. The Muslim side, meanwhile, were depicted as pathetic victims in an equally caricatured fashion.

One British official working with the UN forces in Bosnia recalls how, in late 1993, Bosnian Muslim troops attacked the Croat village of Uzdol in central Bosnia, ‘killing every living thing’. Yet on both the BBC’s six o’clock and nine o’clock news programmes, Kate Adie reported the massacre as yet another atrocity against the Muslims perpetrated by the Croats. She corrected her facts the next day. The same has yet to be done for the rest of the coverage of the Bosnian war.

The Journalism of Attachment achieves the opposite of what its advocates claim. Far from raising public understanding of the horrors of war, their reports mystify what conflicts are really about. By abstracting acts of violence from any wider conflict over political aims, they remove any possibility of people seeing what caused the war. The result of imposing a ready-made Good v Evil framework on every situation is that conflicts can only be understood as the consequence of man’s atavistic, bestial urges. Instead of ‘humanising’ a war, this approach ultimately dehumanises all those involved – and degrades journalism into know-nothing sentimentality in the process.

WHO BENEFITS?

The defects of the Journalism of Attachment are not limited to bad reporting. The demonisation of groups such as the Serbs or the Hutus is not just a matter of name calling. The Journalism of Attachment is ultimately a moral crusade for Western governments, through the United Nations and Nato, to take forceful action against those accused of genocide and war crimes by intervening around the world. The Nato bombing of Bosnian Serb positions in the summer of 1995, and the SAS killing of a Bosnian Serb police chief accused of war crimes in July 1997, were hailed as victories (albeit ‘too little too late’) by the bloodthirsty hawks of the press corps.

This is another dangerous consequence of treating conflicts as moral issues removed from any political context. A careful study of all the forces and circumstances responsible for the civil wars in Bosnia or Rwanda might find that the West’s self-serving interventions had a considerable hand in causing both conflicts in the first place, and in spinning out the bloodshed.

Once that wider context of Great Power diplomacy is ignored, however, and the wars are reduced to the acts of evil East Europeans or Africans, then it becomes easy to turn the West into the potential saviour of the ‘uncivilised’ world, and to demand more intervention against the forces of darkness.

Iraq and save the Kurds from Saddam Hussein marked a turning point in war reporting. It was the occasion on which most of those radical voices which had spoken out against Western intervention since Vietnam did a 180 degree turn and demanded that the US forces and their allies invade. The result of the clamour for intervention was that the US and British governments used force to create ‘safe havens’ for the Kurds in northern Iraq.

The journalists patted themselves on the back and moved out. But those safe havens soon became death traps, where the Kurds were penned in and left exposed to attack not just by Saddam Hussein, but more importantly by the forces of the neighbouring Turkish government – a Nato ally of the very Western states which the media were supposed to have cajoled into ‘saving’ the Kurds. The Kurds have continued to be picked off from both sides since, but their fate has long since dropped off the news agenda as the media circus moved on to Bosnia, and the Bosnian Muslims became the fashionable victims with whom one should be seen.

And what became of the Bosnian Muslims? The media’s lobbying campaign for Western intervention against the Serbs encouraged the Muslims to break agreements and fight on, in the belief that the USA and its allies (all of which acted on the basis of realpolitik rather than moral principle, and none of which ever gave a damn about anybody in Bosnia) would eventually come to their rescue.

This prolonged the war and led to the loss of many thousands of lives. It encouraged the Bosnian Muslim leaders to seek external patrons rather than local solutions, so reducing all three protagonists in Bosnia’s civil war to pawns in a game of Great Power diplomacy. After three years of bloodshed, Nato did intervene with airstrikes against the Bosnian Serbs, aimed at imposing a settlement on Washington’s terms. It may appear that the Bosnian Muslim leaders got what they wanted: an internationally recognised united Bosnia. The media has certainly celebrated that as a victory for the cause of Right.

But the independent, unitary Bosnian state is a paper fiction. It derives its legitimacy from a document, the Dayton agreement, drawn up by US diplomats and imposed at the point of a cruise missile. It functions only because of political, military and economic coercion from outside: its ‘sovereign’ territory is occupied by foreign armies, its ‘democratic’ elections are supervised by foreign officials who dictate who can and cannot run for office, its ‘free’ economy is run by the IMF and the World Bank. If the Bosnian Serbs have been set up as whipping boys by the international media, the Bosnian Muslims have been turned into the West’s patsies by the moral crusaders. All of the peoples of Bosnia have paid a high price for the press corps’ intervention in their affairs.

There are other horror stories to tell about the press corps’ intervention on behalf of the peoples of Africa, where journalists have ‘discovered’ famines and demanded Western action several times in recent years. One excellent recent account of the coverage of the crisis in Somalia at the end of 1992 explains how, by uncritically reporting exaggerated starvation statistics and focusing on the most graphic horror stories (‘for television, the worst, most despairing picture was the best’), the media encouraged the intervention of 30 000 American troops at a time when the worst of the famine had actually been over for months.

The US-led international intervention was an unmitigated disaster which left the country in a far worse mess than when they arrived. And when the American troops pulled out, the journalists detached themselves from the victims and went too, leaving the Somalis to clear up the bloody mess which the ‘caring’ US forces and their helicopter gunships left behind.

The claim that the Journalism of Attachment is about developing a more ‘humanised’ approach to war and disaster and giving the victims a voice simply does not stand up to examination. By no means all victims qualify for the international press corps’ compassion, and the media’s decisions about which ones to adopt and which ones to drop appear fickle, even arbitrary, and subject to outside influences. Clearly there must be something else going on here.

So what is the new school of moralising war coverage really all about? What underlying motives explain the emergence of the Journalism of Attachment in the 1990s? The answer appears to lie, not in the war zones of Bosnia or anywhere else ‘over there’, but in the problems facing the journalists concerned in our societies over here.

A TWISTED SORT OF THERAPY

Strange, isn’t it, that so many Western commentators seem to have become certain about the nature of Good and Evil in the rest of the world, at the same time as everybody is so very uncertain about what Right and Wrong mean today in Western societies themselves’. In Britain, for instance, we are forever being told that there is a need for a new moral consensus, and that our children must be given firm guidelines for life.

At the same time in practice, however, nobody in the press or in politics seems able to reach a consensus as to what is really right or wrong today, on issues ranging from child-rearing to euthanasia, from road-building to genetic engineering. The old institutions which gave society its coherence have all declined in influence and people have lost respect for traditional values.

There is, as many observers have noted, something of a moral vacuum at the heart of Western society today. And it seems that the new breed of journalists has taken it upon themselves to fill it through their mission to the world’s war zones. For those of us who live in complex societies where all of the old values are being called into question, it is no doubt easier to re-establish a sense of certainty about right and wrong in faraway places. This is a key role of the Journalism of Attachment: it is a moral mission on behalf of a demoralised society. When the ethical dilemmas raised by all kinds of social and scientific issues appear both baffling and divisive, the certainties of the Journalism of Attachment can seem welcome and reassuring. For Western societies floundering in moral relativism, the absolutes of Good and Evil portrayed in moving reports from Bosnia, Rwanda and elsewhere can provide a powerful tonic.

The Journalism of Attachment uses other people’s wars and crises as a twisted sort of therapy, through which foreign reporters can discover some sense of purpose – first for themselves, and then for their audience back home. It turns the life and death struggles of others into private battlegrounds where journalists who have lost faith in the old values of their profession can fight for their souls.

The degree to which the Journalism of Attachment is really about fulfilling the needs of the journalists involved is evident from the way in which its reporters often place themselves at the centre of their stories. Since the war in Bosnia began, there have been endless articles in the broadsheets about the role of fearless reporters (especially female ones) as combatants and crusaders, published under headlines like ‘Writing wrongs’, ‘Going over the top’, Women’s war daily’ and ‘Casualties of truth’, the last one a paean to the journalist-as-martyr (‘Anyone can be a victim because warring parties have come to see journalists as legitimate targets’) by the Guardian’s Maggie O’Kane herself.

Martin Bell talks about ‘being shot at’ on assignment (as opposed to being accidentally hit) and has praised the BBC for the way it ‘took its casualties’ in Bosnia, as if the corporation really was an army and he was the mic-carrying equivalent of his hero, Colonel Bob Stewart. Television has weighed in with late-night documentaries about the struggles of the press corps in Sarajevo. The film-makers have also done their bit to dramatise the heroic role of the war reporter as the fulcrum of the conflict: three European feature films about Bosnia, shown at recent international festivals, all chose to view the civil war through the eyes of foreign journalists.

As they hand each other awards as if they were medals, the degree to which the media industry can be obsessed with itself in the middle of somebody else’s war sometimes borders on self-parody. Reviewing a book on Bosnia by Peter Maass of the Washington Post, for example, fellow Bosnian veteran Jonathan Steele of the Guardian talks about Sarajevo’s Holiday Inn, where the world’s press hung out and drank together during the siege, as ‘the centre of Bosnia’s commuter war, the eye of a hurricane’. In his book Love Thy Neighbour, Maass ridicules the war correspondent equivalent of Wall Street’s ‘big swinging dicks’, who strut around like victorious generals, but admits that ‘there’s a bit of it in most of us’.

Steele congratulates Maass, not for any insight into the real Bosnian war (Maass admits he did not go to the battlefields), but for ‘his honesty and skill in dissecting the emotions of the press corps itself’, above all for his ‘micro-picture’ of’ what he and his colleagues felt’. The question as to why an intimate examination of what goes on inside the hack pack’s heads and stomachs should be of interest to anybody except the Holiday Inn regulars does not seem to have occurred to either of them. As Steele concedes, for many of the assembled press corps ‘the war had the fascination of horror porn’ – something removed from reality which the big swinging dicks could watch while working on their private fantasies of stardom.

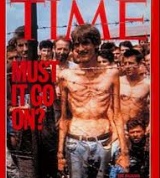

In the world-view of the Journalism of Attachment, the war reporter emerges as an important and singularly moral figure with a sense of decency, in a world sullied by evil abroad and appeasement at home. It is in this spirit that one insider’s account of television coverage of Bosnia suggests that the global impact of ITN’s famous reports from the Bosnian Serb camps in August 1992 was not due only to the image of emaciated Muslims apparently caged behind barbed wire, but equally to the image of ‘brave and intrepid reporters interviewing camp detainees and confronting those who imprisoned them’.

The self-image of foreign reporters as saintly crusaders abroad could hardly be further removed from the traditional view of the press corps as ‘cynical, hard-bitten, hard-drinking hacks, as captured in something like Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop – an image which the journalists themselves once revelled in.

The powerful sense of self-aggrandisement in the new role war reporters have allotted themselves has played an important part in shaping the tone of many recent war reports. If the journalist is to be taken seriously as a crusader for the cause of Right, she cannot be seen messing around in dirty little local wars that don’t matter much to the rest of us. Every conflict she is reporting has to be recast as one of world-historic importance, one that no editor, reader or viewer can afford to ignore.

That is one big reason why many journalists now seem happy to bandy about heavyweight history-making labels like ‘Holocaust’, ‘genocide’ and ‘crimes against humanity’ when describing what are, frankly, brutal but unexceptional civil wars. Prisoners of war and refugee camps are run-of-the-mill stories from any conflict. But ‘discover’ some concentration camps/death camps/gulags and the front pages beckon. Who would care about a report from yet another local ‘ethnic conflict’ in Africa? But make that ‘Eyewitness in Rwanda: an expose of the third genocide this century’, and we are talking world-wide net-worked coverage.

Some foreign reporters are at least aware of the potential perils involved in trying to maintain their new-found star status. Fergal Keane of the BBC World Service typifies the trend for journalists to project their personal hopes and fears onto the foreign wars they report. Keane won international recognition when he used the Rwandan tragedy as the theme of a radio broadcast addressed to his new-born son, about the better kind of world in which he hoped young Daniel would grow up. He has recently written about feeling ‘exhilarated, flattered, amused and frightened’ suddenly to find himself the centre of media attention; but he also noted the danger of foreign reporters getting a taste for the spotlight, to the point where ‘journalism becomes secondary or a mere tool in the business of sustaining one’s celebrity’.’

Others, however, carry on regardless. The fighting in Bosnia has been over for some time, but the Bosnian war which Ed Vulliamy of the Guardian is fighting in his own head and heart continues to escalate in scale and importance, apparently becoming an ever-more epoch-making jihad against Serbian fascism and genocide. It seems that the more evil the Serbs can be made, the more important his personal mission to thwart them will be, and the more meaning there will be to his life. In one article the crusade against fascism in Bosnia even appeared to have become the means through which Vulliamy tried to sort out that perennial source of angst among middle class males; the need to live up to your father’s achievements.

Unlike his Second World War veteran father, however, Vulliamy did not take up arms against the Serb ‘imitation of the Third Reich’ himself, but instead became a laptop bombardier firing a barrage of shrill articles about why others should do so on his behalf.

SAVE THE WORLD

The adherents of the Journalism of Attachment are in serious danger of believing their own puhlicity, and acting as if they really are the beacon of light and honour that can show the squabbling peoples and governments of the world a better way. So Bell speaks of the British as ‘an unled people’, and notes how in Bosnia the Colonel Bobs, the aid workers and the journalists had to find ‘that leadership in ourselves’ rather than ‘pass by on the other side and wring our hands’.

In the USA, meanwhile, one leading advocate of ‘civic journalism’ (a broad equivalent of the Journalism of Attachment focused on domestic issues) suggests that the press should swap its traditional role of ‘watchdog’ for a new role as ‘guide dog’ – an argument based on the assumption that the rest of us are blind to the greater truth which journalists can see, and so we must be led down the path to salvation.

Getting thoroughly carried away with themselves, these people end up implying that the media should go on a moral mission to save the world. Martin Bell thinks that television could have prevented the bombing of Dresden during the Second World War, Roy Gutman suggests that it could have prevented the Holocaust ever happening. (Never mind that blanket television coverage did nothing to stop the Allies bombing Iraq back to the Stone Age in 1991, or that the mass media was the loudest voice calling for Nato to start bombing the Bosnian Serbs.)

And still the self-delusions of grandeur grow apace. Even before he went into politics, Martin Bell liked to boast of how government ministers had to come to him to find out what was going on. The American journalist Peter Arnett, meanwhile, delights in the suggestion that his profession has overthrown governments, in a story which sums up the inflated opinion some journalists hold of themselves today. During the war between Chechen rebels and the Russian army, Arnett recalls how he questioned one guerrilla’s faith that they would win, pointing out that the governments of the world had turned their backs on the Chechens. ‘You are wrong’, replied the Chechen, ‘we have the support of the government of the international media, and you are one of its ambassadors’. The journalist had an intellectual orgasm on the spot:

‘The Government of the International Media – the worst fears come true of all those who in my lifetime have tried to censor, intimidate and lie to the press. It does have a great ring to it.’

It has an especially great ring to it, of course, if you happen to be an international media man attached to the right moral causes to get a seat in the cabinet or an ambassador’s post from the ‘Government of the International Media’. In the USA, critics of civic journalism like veteran editor Michael Gartner have argued that if journalists want to influence events rather than report them, they should go into politics as Bell has since done. These days, however, the self-appointed ambassadors of the press seem to have far more moral authority to dictate what is Right and Wrong around the world than does the discredited class of elected politicians.

Armed with their new status as global statespersons, international journalists like to flatter themselves that they are a radical new broom sweeping the world clean of the old corruptions and evils of power politics. They act out the role of bold campaigners who are going against the grain, putting pressure on the reluctant Western establishment to intervene to prevent genocide and take a stand against crimes against humanity. The bitter irony is, however, that the people who ultimately stand to benefit most from the Journalism of Attachment (apart from the journalists themselves, that is) are the same Western elites and authorities whom it claims to criticise and pressurise. This is what most sharply distinguishes today’s Journalism of Attachment from the campaigning journalism of yesterday.

AMNESIA OR DISHONESTY

There have been many fine campaigning journalists who have taken sides with the oppressed and sought to expose injustice, whether they were writing about America’s war in Vietnam in the sixties and seventies or the British government’s assaults on the mining communities in the eighties. The main aim of these campaigning journalists was to expose the misdemeanours of their own societies. American, British and other Western journalists sought to show how their own governments, which claimed to be free and democratic, were in fact acting as colonial dictators against the Third World, and as class dictators against workers, ethnic minorities and other targeted groups at home. What characterised many of these journalists was their anti-interventionist outlook; they called for US forces to get out of Vietnam and Nicaragua, for the riot squads of the Metropolitan Police to get out of the Yorkshire coalfields, or (more rarely) for the British army to get out of Northern Ireland.

The followers of the Journalism of Attachment take a very different line. Instead of exposing the workings of their own societies, today’s radical reporters are searching for signs of evil in other people’s backyards. And far from criticising the role of the powerful West in creating problems around the globe, they insist that ‘we’ are the only possible solution to the world’s problems. Their criticism of the authorities in Washington and Whitehall is not that they throw their weight around too much, but that they do too little. Wherever there is trouble these journalists demand more political and military intervention, on the grounds that ‘something must be done’ – and if that ‘something’ now means the deployment of SAS death squads against the likes of Bosnian Serbs, so much the better. They are apparently oblivious to the lesson of history which the best of the old campaigning journalists had grasped; that whatever ‘something’ the Great Powers do around the world, it is likely to be at the expense of freedom and justice.

Some of today’s foreign reporters imagine themselves in heroic mode as the few carriers of the torch of honour, a small band of Bravehearts that has kept up a lonely fight against the powerful ‘appeasers’ in the West who refuse to intervene against fascism and evil in foreign crises like those in Bosnia or Rwanda. This notion, that the Journalism of Attachment is swimming against the tide and challenging the status quo, is based either on intellectual amnesia or downright dishonesty.

Take the bizarre claim, constantly repeated by Ed Vulliamy and friends, that the entire ‘international community’ and ‘mass media’ (not the exclusive Guardian, you understand) were at best ‘appeasers’ of Serbian aggression in Bosnia, and at worst downright Serb-lovers. This assertion of pro-Serb bias has gained the status of common sense in influential media circles. Yet where is the thinnest shred of evidence for it?

How many major newspaper articles were written criticising the Bosnian Muslims for their role in the fighting, or telling the stories of Serb victims of the war? Amid their many attacks on the ideology of a ‘Greater Serbia’, how many liberal journalists ever questioned the idea of an intolerant Muslim state being created in the heart of Europe – something the same people seem to find intolerable in Iran or Afghanistan? Name one BBC Panorama programme or ITV World in Action documentary which could seriously be said to have served as a propaganda broadcast for the Serbian cause.

As far as the notion of a Serbophile conspiracy among Western governments is concerned, that fantasy is readily exposed by the fact that the only leading statesman the journalists ever seem able to name as allegedly pro-Serb is the former British Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd. The hapless Hurd has been the butt of article after article from the pro-intervention lobby, as if he were a Bond movie villain single-handedly responsible for endangering civilisation (he was known as ‘Hitler’ Hurd at Eton, after all). Meanwhile, back in the real world of the Bosnian civil war, Bosnian Muslim troops wearing American uniforms, carrying US M-16 rifles and advised by a former Nato supreme commander fought against the Serbs, in an alliance with the Croats that was forged in Washington.

The claim that foreign reporters are battling against the odds in their demands for more intervention is really just another piece of preening by the journalists concerned. It enables them to live out the fairy tale of being literary Luke Skywalkers, fighting the Evil Empire armed only with their sense of decency.

KICKING AT AN OPEN DOOR

The truth is that, in denouncing the pro-Serb appeasers in Western governments, today’s radical reporters have been tilting at windmills. And in demanding more international intervention by the British, American, French or German governments, they are kicking at an open door. Far from putting the authorities under embarrassing pressure, these crusading journalists are actually doing the elites of Western society a service.

The uncertainty and buck-passing which characterised the Western response to the war in Bosnia, for example, was denounced by the new school of war reporting as the Western world’s ‘appeasement of the Serbs…and the betrayal of the Muslims’. In fact what it reflected was the general incoherence of Western foreign policy in the aftermath of the Cold War. With the old certainties of anti-communism gone, the Western alliance found itself without a clear mission in the world and subject to new internal tensions between the USA and Europe. Cut loose from its post-1945 moorings and adrift without clear direction, the Western alliance did not feel capable of organising a decisive intervention in Bosnia – especially in a conflict where, unlike in the Gulf War, there was no obvious route to a quick, cheap victory.

Whatever their intentions, the effect of the crusading journalists’ demand for intervention on moralistic grounds was to help overcome the incoherence of Western foreign policy and give the elites a new rationale for running the world.

The ethical dimension which attached journalists introduced into the foreign policy debate has provided a ready-made sense of direction which governments have proved willing to latch onto in the absence of anything else.

In taking up the cudgels handed to them by the media against the Serbs and the Hutus, Western governments and the international institutions they command have sought to carve out a new righteous role for themselves, re-establishing their right and indeed responsibility to intervene around the globe: not, this time, under the unpopular and outdated flags of empire, but under the worthy riew banners of a UN/Nato crusade against evil in the uncivilised corners of the East and the South. The International War Crimes Tribunal set up at The Hague, and the Anglo-American hit squads deployed against Bosnian Serbs, are forceful demonstrations of the West’s new global authority to dispense summary justice (even on-the-spot death sentences) with the loud support of the media moralists.

So those in the media ‘pressurising’ governments for action are kicking at an open door. Of course governments will not answer every call to intervene, and will not go as far as the media zealots demand. The aim of the authorities in Washington and Whitehall is, after all, to protect their own interests and project their power in the world, not to follow any missionary agenda proposed in the op-ed pages of the broadsheet press. But whether the governments choose to ‘do something’ or not on any particular occasion, the important thing is that the media’s moral crusaders have handed them the authority to do so. Where the campaigning journalism of the recent past challenged the right of the old imperial powers to interfere in the affairs of the rest of the world, the Journalism of Attachment demands that the West takes over the world once more, this time in the name of defending human rights and stopping genocide. Being pressurised to invade small countries by the left-liberal media is the kind of criticism that generals and government ministers can happily live with.

The campaigning journalists who opposed American intervention in Vietnam or Britain’s war in Ireland were driven by the impulse of exposing the powerful. Those journalists who demand Western intervention around the world today are driven by the impulse of promoting themselves. If they think that they are shaking up society’s outlook, they are also kidding themselves. The fact is that British society now demands that its journalists become attached. Anxiety about a moral vacuum, and a preoccupation with the search for moral certainties and a clear sense of right and wrong, is not the preserve of a few self-important reporters. These tensions now influence the way that society and the media as a whole tends to view domestic as well as international issues. Those journalists who transgress against the new moral correctness, and stray outside the Good v Evil framework in their reports, are the ones who can expect to be treated as heretics.

Look what happened to even such a respected BBC journalist as Kate Adie over the Dunblane tragedy. Her reports on the killing of 16 young schoolchildren and their teacher were publicly criticised by a senior BBC executive for being too ‘forensic’. In other words, Adie had assumed her job was to report the hard facts about deaths and injuries, when what her bosses wanted was a mawkish effusion about evil and innocence. In this climate it should be clear that those practising the Journalism of Attachment are not really the radical mould-breakers they claim to be; they are more like placemen, hacks working according to the demands of their editors and owners, who much prefer a sermon to a serious examination of the defects of a society to which they are deeply committed.

The new school of war reporters often likes to contrast its work in Bosnia to the media coverage of the 1991 Gulf War.

The common view is that, back then, they were duped and manipulated by the American, British and Kuwaiti governments, which censored the news and got the media to broadcast propaganda myths as fact. ‘This is a tale of how to tell lies and win wars, and how we, the media, were harnessed like beach donkeys and led through the sand to see what the British and US military wanted us to see in this nice clean war’, wrote Maggie O’Kane in an article which ‘exposed’ some of the dirty lies which the media had broadcast about Iraqi Muslims – although it apparently took her until five years after the Gulf War to realise that she had been had.

But, they assure us, things were very different in Bosnia, where independent-minded reporters could roam free and report the truth. The truth is, however, that censorship was unnecessary in Bosnia, since the press corps proved willing and able to ‘manipulate’ itself. By striking lofty moral poses and appointing themselves as spokespersons on high for the victimised and the oppressed, the war reporters excused themselves from the hard groundwork of sifting propaganda from fact. They turned the complicated realities of Bosnia into a clean-cut fairy tale of good and evil without any help from the censors. Maybe five years after the end of the war in Bosnia, Maggie O’Kane will write a reveal ing feature about how they were ‘harnessed like beach donkeys’ by the press officers of the Bosnian Muslim government and its American allies. Or maybe not.

HAPPY NEWS IS HERE AGAIN

Those who pursue the Journalism of Attachment, whether explicitly or implicitly, are playing a dangerous game for high stakes. The language of evil, genocide and Holocaust can exact a high price from the accused. Such a substitution of emotion and histrionics for rational and critical analysis must also prove a major setback for standards of journalism.

For all their talk of the need for serious, unsanitised coverage, the irony is that they are providing a new form of Happy News coverage of international affairs. The obsession with finding human interest stories about the suffering of the victims of evil has gone so far that it has even created an international equivalent of the ‘And finally…’ domestic news stories about cats and dogs; instead of animal rescue stories, the foreign press corps gave us the tale of how ITN newsman Michael Nicholson smuggled home the orphaned Natasha from Bosnia, and the dramatic story of how Baby Irma was flown out from Bosnia to be treated on the British NHS.

It is an approach that can only sentimentalise reality, and detract from the real tensions and struggles underlying conflicts around the world. Instead of understanding the complexities of power politics that create wars and crises, the fashion is to reduce everything in advance to a childish scenario of good and evil with which everybody can be comfortable, and nobody need worry about having their prejudices challenged. All we have to do is sit back in our seats, cheer the good guys and boo the villains.

What began with Martin Bell’s call for a journalism which ‘cares as well as knows’ effectively ends up with the attitude that ‘who cares what we really know, so long as the world knows that we care’. ‘The truth is our currency’ was the title Martin Bell gave to his series of four talks on Radio 4, broadcast in the spring of 1997, in which he put forward his case for a Journalism of Attachment. Yet the final consequence of the new school of foreign reporting is to make it harder to get at the whole truth, by stifling critical discussion of controversial issues and outlawing opinions which offend against the moral party line.

The attempt to redefine issues in terms of Good and Evil allows no space for reasonable debate. Those who are not wholeheartedly on the side which the journalists adjudge to be Good must be treated as if they were the agents of Evil. That is why anybody who doubts the wisdom of military intervention in Bosnia risks being branded an ‘appeaser’, while anybody who dares to question the demonisation of the Serbs can expect to be accused of ‘revisionism’ or even ‘Holocaust denial’ – the modern equivalents of blasphemy. This has been the experience of LA magazine in our libel battle with ITN and its allies over our publication of revelations about their award-winning pictures of Bosnian-Serb run camps.

Many journalists and others are unhappy about the drift of foreign reporting and the assumptions behind the Journalism of Attachment. Yet there remains a resounding silence on this taboo subject. It is time somebody took a stand for a journalism that is campaigning yet crit ical, that takes sides but tells it like it is, and that will not compromise on the need for full and open discussion of all the facts as our only chance of getting at the truth.

Journalists must have the freedom to think for themselves; to refuse to join in fashionable witch-hunts; to question everything, especially the moronic notion that important political issues can be reduced to morality plays or human interest stories; and to offend against the moral correctness which says that those branded evil should be deprived of a voice. If we are to preserve that freedom something-must-be-done about the drift into the Journalism of Attachment.

Footnotes

1] ‘In place of the dispassionate practices of the past I now believe in what I call the journalism of

attachment. By this I mean a journalism that cares as well as knows; that is aware of its responsi-

bilities; and will not stand neutrally between good and evil, right and wrong, the victim and the

oppressor… We exercise a certain influence and we have to know that. The influence may be for better

or worse and we have to know that too.’, Martin Bell, ‘TV news: how far should we go?’, British

Journalism Review, Vol 8 No 1, 1997.

2] ‘We can’t watch passively while people are being killed in front of us. There are higher require-

ments. As a reporter, you can’t simply sit there and report passively. You’ve got to do everything

in your power to stop these things, and exposing it is one of the best ways to do it.’, Roy Gutman,

interviewed in American Journalism Review, June 1993.

“I have come to believe that objectivity means giving all sides a fair hearing, but not treating all

sides’equally. Once you treat all sides the same in a case such as Bosnia, you are drawing a moral

equivalence between victim and aggressor. And from here it is a short step to being neutral. And from

there it’s an even shorter step to becoming an accessory to all manners of evil….0bjectivity must go

hand in hand with morality.”, Christiane Amanpour, Quill, April 1996.

Introducing his book on Bosnia, Ed Vulliamy rejects the ‘bizarre requirement that we

remain “objective” over the most appalling racialist violence. There is no attempt here to be objective

towards the perpetrators of Bosnia’s ethnic carnage or those who appeased them’, Seasons in Hell,

1994, pxi.

3] ‘I wish you to know that good and evil are not abstractions, but active forces in the world out there.

I wish you to know that the old adage holds true today, more than ever, that all that is necessary

for the triumph of evil is for good people to do nothing…l wish you to know that genocide is not an

unaccompanied crime. It requires accomplices, not only the evil and brutality and ignorance which

make it happen, but the indifference which lets it happen. That was so 55 years ago, and it still is

today.’, Martin Bell, from a speech at ‘Remember the Past, Learn from the Present, Look to the

Future’, an event organised by Jewish Care, the Independent and Penguin Books, 1 September 1996.

4] ‘To what do reporters decide to be attached? Are most wars, especially today’s civil conflicts,

so open to judgement as to which side is right, which wrong? Are reporters able to point to the

original sin and the unsullied virtue? Is it so clear to reporters – whose job includes getting through

war zones, making sure they can get their transmissions out, competing with rivals for the most

graphic shot – what is good and what is evil, day by day?’ John Lloyd, Prospect, July 1997.

5] Andrew Thompson, iVewsnight, letter to the Spectator, 12 March 1994. Nik Gowing quoted in the

LA Times, 22 April 1997.

6] Washington Post journalist Peter Maass, Love Thy iVeighbour: A Story of War, 1996.

7] Ed Vulliamy, ‘The art of war: is the truth about Bosnia found in the camera’s lens or the mind’s

eye?’, New Statesman, 25 April 1997.

8] Martin Bell, In Harm’s Way: Reflections of a War-zone Thug, 1996, p151.

9] Roy Gutman admits that, when he wrote the famous Newsdayreport in which he first claimed that

the Bosnian Serbs were running Nazi-style ‘death camps’ (2 August 1992), he did not bother fully to

check the facts of horror stories that he had been told, because he was in a hurry to tell the world

‘the truth’, American Journalism Review, June 1993.

‘During last Thursday’s opening item on what was repeatedly said to be “systematic and organised

rape” in Croatia (a horror tale told about French victims in the First World War and Belgians in World

War Two) it turned out that ITN could produce not one single woman who would substantiate the

story.’, Christopher Dunkley, ‘Glitz threatens the News at Ten’, Financial Times, 23 December 1992.

10] Deutsche Presse-Agentur report, 6 June 1996. Akashi said that only one journalist – the

American David Binder – had actually seen fit to quote from the ‘secret’ report in print.

11] These events were the subject of Clive Gordon’s award-winning documentary, The Unforgiving,

Channel 4, August 1993.

12] Stockholm International Peace Institute, Annual Report, 1996.

13] John F Burns, ‘A killer’s tale – a special report’, New York Times, 27 November 1992 (later

reprinted in the Guardian and the Daily Mail); Maggie O’Kane, ‘A public trial in Bosnia’s sniper

season’, Guardian Weekly, 21 March 1993.

14] Ed Vulliamy has previously objected to my suggestion that an attachment to something other

than the facts at hand might have coloured his award-winning reports trom Bosnian Serb-

run camps, which he visited with an ITN team in August 1992. ‘The reference to “attachment” is

particularly odious. Proper, professional journalism as practised by ITN and the Guardian is always

objective. Objectivity is fact-specific; we report what we see; we certainly did so that day.’ (‘I stand

by my story’, Observer, 2 February 1997.) Perhaps the outraged Vulliamy could explain why his

reports of what he saw at Trnopolje camp on 2 August 1992 have changed at least five times over

the past five years. For one who puts such emphasis on the authority of the eye-witness, Vulliamy

seems to have a lot of trouble recalling exactly what it was his eyes witnessed. For the details, see

Mick Hume, ‘Ed Vulliamy’s recovered memories’, LM, March 1997.

15] Rakiya Omaar, Guardian, 30 April 1997. For a full account of how the demonisation of the

Hutu refugees led to the tragic events of spring 1997 in Zaire, see Bernadette Gibson, ‘Blood on

whose hands?’, LA1,lune 1997.

16] Quoted in Louisa Sanders, ‘Writing wrongs’, Guardian, 30 March 1993.

(17 & 18 missing from file copy)

19] Quoted in Sandra Harris ‘On top of a troubled world’, High Life, June 1997.

20] ‘The political context just qeems so irrelevant when you’re out in the field… Whether you want to

or not, you become what is called a colour writer, because you become involved in events, you care

about the people, you’re scared a lot of the time. You don’t think about the political context, or your

political views become really simple.’, Andrej Gustincic, Guardian, 18 January 1993.

21] ‘Journalists at war’, 1993.

22] Guardian, 5 August 1995.

(23 & 34 missing from file copy)

25] See ‘Feeding the famine’, in Michael Maren, The Road to Hell: The Ravaging Effects of Foreign

Aid and International Charity, 1997, pp203-215.

26] ‘Going over the top‘, Guardian, 18 January 1993; Louisa Sanders, ‘Writing wrongs’, Guardian, 30

March 1993; Nick Gordon, ‘Women’s war daily’, Sunday Times, Style and Travel, 27 June 1993; Maggie

O’Kane, ‘Casualties of truth’, Guardian, 3 January 1994.

27] Welcome to Sarajevo (UK), II Carniere (Italy), and Territorio Comache (S pain)

28] Johnathan Steele, ‘Room with a view of war’, Observer, 14 June 1996.

29] From the editors’ introduction to Bosnia by Television, James Gow, Richard Paterson and Alison

Preston (eds), 1996, p4.

30] Fergal Keane, ‘Famous for a bit’, Guardian, 23 June 1991.

31] ‘My father was a pacifist too, and a conscientious objector at the start of World War Two, until

he realised that war against fascism had to be fought, and he became a reluctant solider, and a

captain in the British Army. I too have changed my mind. ‘Ironically, the horrors of war have taught

me that there are things that are worse than war, and against them determined and careful war

should be waged, in the name of the innocent and the weak. My father had the honour of fighting

fascism; I have instead the strange privilege of meeting the people who are fighting a pale but

unmistakable imitation of the Third Reich but have only the sons of the appeasers of 1938 to turn

to.’ Ed Vuliiamy, ‘A destiny worse than war’, Guardian Weekend, 10 April 1993.

32-‘Remember the past…’, 1 September 1996.

33] Ed Feuhy, Freedom Forum meeting, Arlington Virginia, 9 December 1996.