HOW THE WORLD WAS WON OVER

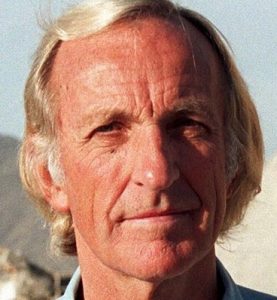

by John Pilger from his book ‘Distant Voices’, 1992

IT IS ONE year since the United States and its coalition

allies attacked Iraq. The full cost has now been summarised

in a report published by the Medical Educational Trust іn

London. (92) Up to a quarter of a million people were killed or

died during and immediately after the attack. As a direct

result, child mortality in Iraq has doubled; 170,000 under-

fives are expected to die in the coming months. This estimate

is described as ‘conservative’; UNICEF says five million

children could die in the region.

More than 1.8 million people have been forced from their

homes, and Iraq’s electricity, water, sewage, communi-

cations, health, agriculture and industrial infrastructure have

been ‘substantially destroyed’, producing ‘conditions for

famine and epidemics’. Add to this the equivalent of a natural

disaster in 40 low-and middle-income countries.” (93)

How were these historic events set in train? Forgotten facts

tell us much. On October 29, 1990, US Secretary of State

James Baker declared, ‘After a long period of stagnation, the

United Nations is becoming a more effective organisation.

The ideals of the United Nations Charter are becoming realit-

ies.’

Within a month Baker had tailored the ideals of the UN

Charter entirely to suit American interests. He had met the

foreign minister of each of the 14 member countries of the

UN Security Council and persuaded the large majority to vote

for the ‘war resolution’ – 678 – which had no basis in the

UN Charter.

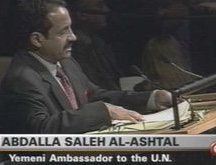

Such a vote, remarked Yemen’s UN Ambassador

Abdallah al-Ashtal, was inconceivable without ‘all kinds of

pressures — and inducements’. (94)

So came about the dawn of what is celebrated by Western

commentators as the United Nations’ ‘new age’. In fact, it

was one of the most shameful chapters in the Organisation’s

history. For the first time, the full UN Security Council

capitulated to the War Party and abandoned its commitment

to advancing peaceful and diplomatic solutions.

Throughout the crisis, the UN Security Council ignored and

contravenedits own charter; it merely served up the appearance

of inter-national legality, a truth that became spectacularly

clearwhen the bombing began in January. It was then that the

United States withdrew its embrace of the United Nations

and actively, and illegally, prevented the Security Council

from meeting.

But this degree of control was possible only through a

campaign of bribery, blackmail and threats. It is no secret

that rewards were provided to certain Arab states for their

participation in the ‘coalition’. US News and World Report,

in an article entitled ‘Counting on New Friends’, described

how James Baker had ‘cajoled, bullied and horse-traded his

way’ to get Resolution 678 through the Security Council.

Several of the larger deals — for example, the ‘inducements’

to Egypt and China — were widely publicised. (95)

Some commentators even expressed moral qualms about

‘distasteful bargains’ with the ‘butchers of Beijing’, the

‘loathesome Assad’ and other unsavoury clients, although the con-

cern was clearly that such deals might impede the course of

US war policy; the tactics themselves were barely questioned.

Thus, the full extent of the deals has remained secret. For

the record, I offer here a beginner’s guide to the greatest

bribes in history.

Turkey. Right from the beginning the Turkish regime knew

that it was on to a winner. Based just across the border,

American planes could bomb Iraq with impunity. By November

3, 1990, the promised booty was pouring іп and President

Turgut Ozal celebrated in a public address. ‘In a way,’ he

Said we have benefited from this crisis and made very

significant progress towards our goal of modernising and

strengthening our armed forces’. (96)

Ozal boasted that Turkey received at least $8 billion worth

of military gifts from the United States, including tanks,

planes, helicopters and ships. According to Steve Sherman of

Middle East International, the United States also pledged to

speed up the delivery of Phantom bombers delayed by the

pro-Greek lobby in Washington; and the US Export Import

Bank agreed to underwrite the construction of a Sikorsky

helicopter factory in Turkey: itself worth about a billion

dollars to the Turkish regime.” (97)

In his November 3 speech President Ozal said: ‘We are on

the brink of finding new markets for Turkish goods and

Turkish industry.’ Five days later Turkey was told that its

quota of US textile exports would increase by 50 per cent.

At Washington’s urging, the World Bank and International

Monetary Fund (IMF) ‘freed up’ some $1.5 billion in low-

cost loans to Turkey and dropped the initial condition that

the government would have to cut subsidies. George Bush

personally promised to back Turkey’s application to join

the European Community, which still has questions about

Turkey’s human rights record.” (98)

There were ‘human rights pay-offs’ too. Just because Bush

and Major suddenly adopted, and almost as quickly dropped,

the Iraqi-battered Kurds did not mean they would show

concern for the treatment of Turkish Kurds. The routine

persecutions carried out by the Turkish regime continued

unnoticed; and continue today.

Egypt. In 1990, Egypt was the most indebted country in

Africa and the Middle East. According to the World Bank,

the government of President Mubarak owed nearly $50

billion.” (99). Baker offered a bribe, or ‘forgiveness’ of $14 billion.

Under pressure from the United States, other governments —

Saudi Arabia and Canada among them – ‘forgave’ or post-

Poned most of the balance of Egypt’s debt. (100)

Syria. The main exchange in the deal with President Hafez

Assad was Washington’s go-ahead for him to wipe out 6

Opposition to Syria’s rule in Lebanon. To help him achieve

this, a billion dollars’ worth of arms aid was made available

through а variety of back doors, mostly Gulf States. (101) Although

on America’s list of ‘sponsors of terrorism’, Assad and his Ba’athist

fascists — not dissimilar to Saddam Hussein’s fascists — were

given a quick paint job in time to supportAmerica’s war. ‘Photo

opportunities’ were arranged with Baker and Bush; the locked smiles

told all, as ‘old friends were reunited. (102)

Israel. The ‘pacification’ of Israel was vital if the United

States was to preserve its Arab ‘coalition’. The regular $5

billion America gives to Israel clearly was not going to be

enough; and Israeli Finance Minister Yitzhak Modai told US

Deputy Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger that Israel

wanted at least another $13 billion. Israel agreed to a down-

payment of $650 million in cash, and to wait for the $10

billion loan guarantees until later. This partly explains why

the Israelis appear not to give a damn about current American

‘warnings’ as they expel still more Palestinians and build still

more homes for Russian Jews in the occupied territories.’ (103)

Iran. In return for Iran’s support in the blockade of Iraq,

America dropped its opposition to World Bank loans. On

January 9, Reuter reported that Iran was expected ‘to be

rewarded for its support of the US . . . with its first loan from

the World Bank since the 1979 Islamic revolution’. The Bank

approved $250 million the day before the ground attack was

launched against Iraq.

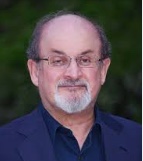

Last November, Britain restored diplomatic ties with Iran,

in spite of the fact that the death sentence on Salman Rushdie,

a British citizen, had just been reaffirmed.

Soviet Union. With its wrecked economy, the Soviet Union

was easy prey for a bribe — even though President Gorbachev

strongly preferred sanctions.

The Bush administration регsuaded the Saudi Foreign Minister,

Sa’ud al-Faysalwe, to go to Moscow and offer a billion dollar

bribe before the Russian winter set in. (104) Once Gorbachev had agreed

to Resolution 678, another $3 billion materialised from other Gulf

states: The day after the UN vote, Bush announced that the United

States would review its Policy on food aid and agricultural

credits to the Soviet Union. (105)

The Soviet Union’s impotence in the face of this degree of

American pressure was illustrated when an American

reporter, Phyllis Bennis, cornered the Soviet Ambassador to

the United Nations, Yuli Vorontsov, in а lift the night the

American bombing started. She asked him if he was concerned

that a war was being fought in his government’s name

He replied with a sigh: ‘Who are we to say they should not?’ (106)

China. In exchange for China’s vote on Resolution 678,

the United States arranged China’s return to diplomatic legit-

imacy. The first World Bank loan since the Tiananmen

Square massacre was approved. On November 30, the day

after the UN vote, Foreign Minister Qian Qichen arrived in

Washington for a ‘high profile’ meeting with Bush and Baker.

More photo Opportunities; more frozen smiles. Within a

week, more than $114 million of World Bank money was

deposited in Beijing. (107)

The impact of the bribes inside China was explained by

the scholar Liu Binyan. ‘For quite some time’, he said, ‘there

has been much talk of formal charges and trials being brought

against the dissidents, but the pressure from abroad pre-

vented it. Since August, however, Beijing has skilfully

manipulated the Iraqi crisis to its advantage and rescued itself

from being the pariah of the world.’ (108)

The vote of the non-permanent members of the Security

Council was crucial; and the following bribes. and threats

were successful. Within a fortnight of the UN vote, Ethiopia

and the United States signed their first investment deal fог

years; and talks began with the World Bank and the IMF.

Zaire was offered US military aid and debt ‘forgiveness and

in return acted for the United States in silencing the Security

Council after the war began. Occupying the rotating presidency

of the council, Zaire refused requests from Cuba, Yemen and India

to convene the Security Council, even though it had no power to

refuse them under the UN Charter. (109)

Only Cuba and Yemen held out. Minutes after Yemen voted

against the resolution, a Senior American diplomat was

instructed to tell the Yemeni ambassador, ‘That was the most

expensive “no” vote you ever cast.’ Within three days, a US

aid programme of $70 million to one of the world’s poorest

countries was stopped. There were suddenly problems with

the World Bank and the IMF; and 800,000 Yemeni workers

were expelled from Saudi Arabia. The ‘no’ vote probably

cost Yemen about a billion dollars, which meant inestimable

suffering for its people. (110)

The ferocity of the American-led attack far exceeded the

mandate of Resolution 678, which did not allow for the

destruction of Iraq’s infrastructure and economy. The law-

lessness did not end there. Five days after 678 was passed,

the General Assembly voted 141 to 1 reaffirming the ban on

attacks on nuclear facilities. On January 17, the United States

bombed nuclear facilities in Iraq, including two reactors

twelve miles from Baghdad.

When the Security Council finally convened a meeting in

February, the United States and its allies forced it to be held

in secret, one of the few times this has ever happened. And

when the United States turned back to the United Nations,

seeking another resolution to blockade Iraq, the two new

members of the Security Council were duly coerced. Ecuador

was warned — by the US ambassador in Quito — about the

‘devastating. economic consequences’ of a no vote. Zim-

babwe, whose foreign minister had earlier described the resol-

ution as ‘a violation of the sovereignty of Iraq’, finally voted

in favour after he was reminded that in a few weeks’ time he

was due to meet potential IMF donors in Paris. Neighbouring

Zambia has had great difficulty negotiating IMF loans — in

spite of democratic reforms. Zambia opposed the resol-

ution. (111) The punishment was most severe against those

impoverished countries that supported Iraq; Sudan, though

in the grip of a famine, was denied a shipment of food

aid. (112)

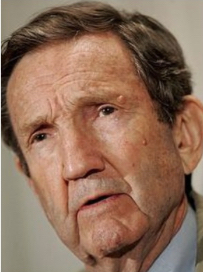

The other day I interviewed Ramsey Clark, whose war crimes

commission has sought to establish the illegality of

the Gulf War. ‘Not only were the articles of the United Nations

Disregarded’ he said, ‘but every article of the Geneva

Convention was broken.

Of course it’s not easy to persuade people to stand up

against power: but when they do, there are successes.

During the Vietnam War the issue of legality prevented

military personnel going who did want to go, and

defended the publication of the Pentagon Papers, which

gave us much of the truth about the war. What we need

urgently is a permanent international tribunal, indepen-

dent of the UN and similar to the International Court

of Justice. Without that, we shall always have victor’s

justice, the perpetrators of crimes will never be called to

account and there will be more and more illegal wars.

None of these issues was widely debated before, during or

after the Gulf War. Getting Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait

skilfully and without putting to death thousands of people —

the same people who were oppressed by him — was only of

marginal interest to the Western media. Censorship was, |

always, less by commission than omission.

As Peter Lennon later wrote in the Guardian:

‘War engenders corruption in all directions. As the

broadcasters were arranging the terms of the stay in

Saudi Arabia, Amnesty published an account of torture,

detention and arbitrary arrests by the Saudis. Twenty

thousand Yemenis were being deported every dey –

up to 800 had been tortured or ill-treated. Neither the

BBC nor ITV reported this . . . It is common knowledge

in television that fear of not being granted visas was

the only consideration in withholding coverage of that

embarrassing story.’ (113)

Other media people who sat red-eyed in studios dropped

the last veil of their ‘impartiality’. Who can forget,

On the first day of the bombing, the Sir Michael and David

Show on BBC Television? There sat David Dimbleby with

Sir Michael Armitage, former head of Defence Intelligence,

as if they were in their club. Sir Michael’s distinguished

career made him an expert on black propaganda in the cause

of Queen and Country; and here he was being offered up as

source of information to the British people. The British,

opined Sir Michael, were super and brave, while the Iraqis

were ‘fanatics holding out’.

For his part, Dimbleby could barely contain himself, He

lauded the ‘accuracy’ of the bombing as ‘quite phenomenal’,

which was nonsense, as we now know. Only a fraction of

the bombs dropped on Iraq hit their target. Where was the

broadcaster’s professional scepticism?

Growing ever more excited, Dimbleby interviewed the

American ambassador to Britain and declared that the ‘suc-

cess’ of the bombing ‘suggests that America’s ability to react

militarily has really become quite extraordinary, despite all

the critics beforehand who said it will never work out like

that. You are now able to claim that you can act precisely

and therefore — to use that hideous word about warfare –

surgically!’ Thereupon Dimbleby pronounced himself

‘relieved at the amazing success’ of it all. (114)

Fortunately, there are some journalists who see their craft

very differently. Thanks to Richard Norton-Taylor, David

Pallister, Paul Foot, David Hellier, Rosie Waterhouse, David

Rose and others, we can now comprehend the scale of the

duplicity and hypocrisy that underpinned the ‘famous victory’.

We now know that the British Government allowed British

firms to break the embargo against Iraq: to continue produc-

ing vital parts for the famed ‘supergun’ and other weapons

supplied to Iraq only months before Saddam Hussein invaded

Kuwait. We now know that shells for the guns that were

trained on British troops came from British-made machines.

We now know that, in spite of an investigation by a House

of Commons Select Committee, there was and remains a

cover-up of ministerial wrong-doing. (115)

This no more than mirrors the cover-ip by those who ran the 8

war in Washington. Thanks mostly to one maverick

Congressman, Henry Gonzalez, chairman of the House Bankng Committee,

we now have detail of how George Bush, as president and vice-president,

secretly and illegally, set out to support and placate

Saddam Hussein right up to the invasion. According to classified

documents, Bush personally directed the appeasement of Saddam

and misled Congress and US intelligence was secretly fed to

Saddam. ‘Behind closed doors,’ says the Gonzalez indictment:

‘Bush courted Saddam Hussein with a reckless abandon

that ended in war and the deaths of dozens of our brave

soldiers and over 200,000 Muslims, Iraqis and others.

With the backing of the President, the State Department

and National Security Council staff conspired in 1989

and 1990 to keep the flow of US credit; technology and

intelligence information flowing to Iraq despite repeated

warnings by several other agencies and the availability

of abundant evidence that Iraq used [US bank] loans to

pay for US technology destined for Iraq’s missile, nuclear,

chemical and biological weapons programmes.” (116)

It is clear that in the summer of 1990 George Bush believed

that Saddam Hussein — his ‘man’, the dictator he backed

against the mullahs in Iran and trusted to guard America’s

interests — had betrayed him. It also seems clear Bush believed

that if his appeasement of Saddam ever got out, the invasion

of Kuwait might be blamed on him personally – hence the

magnitude of his military response. To cover himself, the

price was carnage, which he described as ‘the greatest moral

crusade since World War Two’.

January 17, 1992 to May 1992

Footnotes